Mirembe sits under the shade of her fish stall at the fresh market covering herself from the sun. She sells delicious fresh Mukene and Tilapia. She is just one of the many key actors in the fish value chain which allows this fresh catch to reach customers all over the world. This intricate fish value chain provides a primary source of income and livelihood to 1.5 million Ugandans. It is the second largest foreign exchange earner after coffee in Uganda, receiving investments of $200 million annually. The fishing sites are located on the shores of Uganda’s five main lakes, Victoria, Kyoga, Albert, Edward, and George, which cover 18% of the country’s land mass.

So how does this savoured Nile Perch and Tilapia go from Ugandan lakes to our plates?

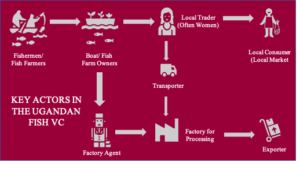

There are a few key actors in the fish value chain who make this process possible. Starting with Ugandan fishermen (often known as Barias) and farmers, the fish travels through the hands of fish farm and boat owners, local traders, transporters, factory agents, factory processors and exporters.

Yet these actors face many issues in managing their day-to-day operations:

- Access to management information: Barias, boatowners, fishermen, local traders and factory agents in the fishing community do not have key business information on daily weather conditions, market price of fish and tracing of fish stock. This hinders their ability to maximise resources and sell competitively in the market.

- Obtaining a fishing licence: In recent years the Ugandan government has tightened their policies on illegal fishing therefore it is mandatory for barias and fishermen to gain a fishing licence. Without this licence they cannot fish, sell their stock and generate income. Unfortunately there is currently no fast and reliable means of applying, paying for and gaining fishing licenses. Fishermen end up spending hours travelling to urban centres, waiting in queues and filling up paperwork for licenses. Some use middle men to navigate through the process. However they often get charged a high fee.

- Infrastructure: Fish landing sites lack essential infrastructure such as concrete slabs, ice plants, fish drying racks, and potable water supply. Roads leading to landing sites have poor infrastructure. This causes fish to get contaminated and rejected from the factory and thereby lowers the income for actors.

- Climate Change: Unsustainable fishing and aquaculture practices are leading to depletion in fish stock. Furthermore due to global warming, water bodies face rising levels due to heavy rainfall. This is causing landing sites to be flooded and swept away by Sudds.* This is affecting the entire fish value chain as there is less stock to sell.

Additionally the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the fish value chain players, further affecting their operations. Curfews and lockdowns have limited fishing hours every day. This has led to low catch, therefore lower volumes of fish sold in local markets and reduced income for value chain actors.

However these main challenges could be overcome with access to tailor made financial services. Fish Value Chain actors need solutions that help them build credit history and access financial channels that will help them improve their personal financial health and business management. For example access to credit will allow them to invest against infrastructure problems or access to insurance products will allow them to secure protection against bad weather. Yet the uptake of financial services have some key barriers in the current situation.

- Financial Awareness and Literacy: At the fish landing sites, Mobile Money and Banking agents are present though there is limited uptake of these agents due to low awareness of the variety of loans and savings products/ services that are offered by these channels. When used, fish value chain actors are dependent on agents to conduct transactions (payments and transfers) on their behalf, due to low financial literacy. This, at times, leaves them vulnerable to frauds. Customers unknowingly pay high transaction charges to agents which further disincentives them to use digital solutions. Added to this they face liquidity inadequacies at the agent outlet, which results in an inability to access transformative amounts of cash.

- Dependency on informal institutions: Barias, boatowners, fishermen and local traders rely mainly on informal options, the most popular being Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLAs) and Savings and Credit Co-Operatives (SACCOs), where savings are pooled together and rotated to pay for assets. These have inconsistent processes of paper based record keeping and ability to lend only small, non-transformative amounts. Especially during COVID-19, they are unable to meet. Formal Institutions such as banks and ATMs are often far from the landing site. Fisherfolk have to travel considerable distances, bear transportations expenses and wait in long queues to access basic financial services. In particular, to access savings and loans services banks have strong Know Your Customer requirements. Using traditional institutions all their lives, fisherfolk don’t have access to documentation and credit history, making it difficult to access products.

To counter these financial challenges, digital finance can play a key role in bridging the gap to financial inclusion and ease access to more formal financial services.

Creative solutions deployed during the COVID-19 crisis have shown that this is more than possible. Airtel and MTN, two of the eight mobile money operators operating in Uganda, have reduced customer fees for small Mobile Money payment transactions below 50,000 ugandan shilling due to COVID-19. This was done to discourage people from using cash in order to encourage social distancing. This has led to an increase in the use of Mobile Money Wallets to pay for goods and services such as groceries, conducting P2P direct transfers. In Masaka, fishermen have digitized their savings groups by now using Mobile Money to encourage members to continue making weekly savings contributions. They each have individual wallets and send the money to the group leader, who then distributes to those who need.

Likewise, implementing innovative solutions to digitize operations and processes of VSLAs and SACCOs can allow fisherfolk to build credit history. Solutions like this can be implemented as private initiatives by companies such as fintechs and insurtechs. They can provide innovative and client centric digital financial services. Combining private players solutions with resources from public entities can enhance the quality of impact. For instance, using credit history (from digitized VSLAs) with identification documents (increasingly distributed to fishing communities by the government’s National Identity Cards programme), can allow fishermen to open bank accounts and access formal products. This makes them better financially included.

Despite a current poor state of physical infrastructure, the government is working to improve the condition present and many landing sites have access to electricity and a good quality network (ranging from 2G to 4G). This is leading to increase mobile phone penetration, especially with the lowering of the cost of devices. These digital channels can help in the dissemination of information on weather, market price transparency and location tracking of fish stock to fisherfolk. Furthermore in collaboration with the Ugandan government, solutions to digitize the process of fishing license can ensure smooth and transparent payment of fishing licence fees for the fish value chain actors and smooth and transparent revenue collection for the government .

Identifying key areas for improvement and driving the implementation of digital financial platforms can enable growth in the livelihood of all stakeholders across the Ugandan Fish Value Chain. It will lead to financial inclusion but most importantly it will allow for social and economic integration of the local population.

For more information view our webinar and published case study report.

* Floating vegetation/ papyrus that has disintegrated from the mainland or island due rising water levels